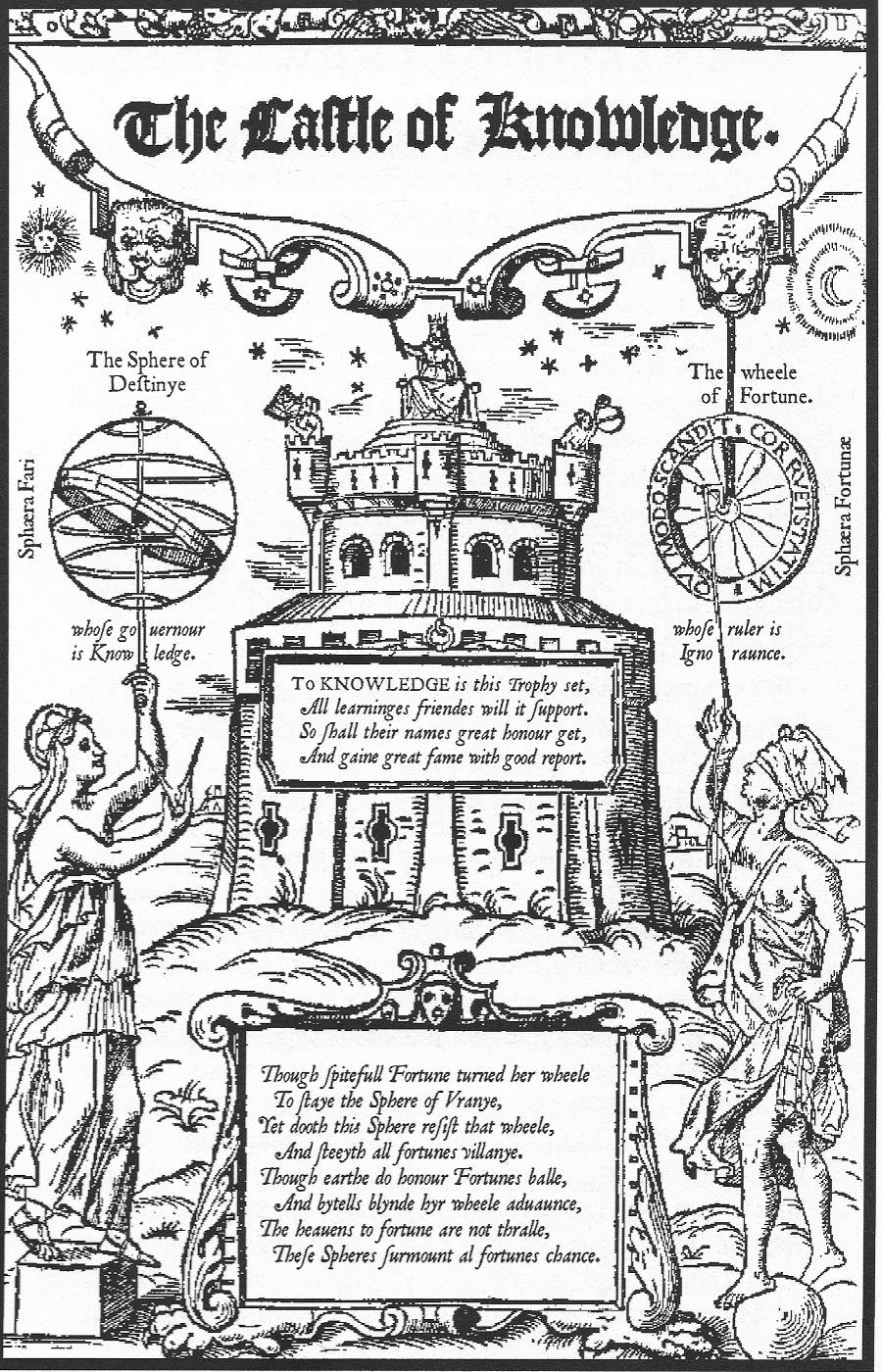

Recorde, Robert. The Castle of Knowledge (1556)

About the Author

Robert Recorde (ca. 1510-1558) was a Welsh mathematician and physician. He studied at Oxford and Cambridge and became a mint administrator under King Edward VI in June 1549.

Although he supported Protector Somerset against the King and was confined to court for sixty days just a few months later, he was appointed surveyor of the mines and monies in Ireland in 1551. However, as the silver mine project under his supervision failed and he came into conflict with William Herbert, the later Earl of Pembroke, he was recalled in 1553. After losing a lawsuit against the very same in 1557, Recorde was sentenced to a fine of £ 1000. Unable to pay the sum, he was put in debtor’s prison and died there the year after.

While not much is known about his private life, Recorde had a rather substantial scholarly oeuvre. He studied Greek and Old English, wrote about religious and political issues, British history and medicine. His most widely remembered works, however, deal with mathematics. His first book, The Grounde of Artes (1543), was an introduction to arithmetic and went through at least forty-five editions up to 1699, and his last work, The Whetstone of Witte (1557), is commonly credited with introducing the ‘+’ and ‘-‘ signs to England and inventing the ‘=’ sign.

In writing his textbooks, Recorde gave considerable thought to didactic order and presentation. He wrote in vernacular and preferred the dialogue form, guiding the reader through the material and to knowledge instead of just presenting it – much like Plato did.

© Thomas Gordon Roberts 2009

The Book

The Castle of Knowledge is special for three reasons: for one, it is the oldest surviving original English astronomy book, not merely a translation or abstract of Latin medieval or classical works. Secondly, it is simultaneously one of the first English books on astronomy that mentions and comments on Copernicus’ De revolutionibus orbium caelestium (1543) and the heliocentric system presented therein. Thirdly, and perhaps even more relevant in the context of this study, Recorde not only refers to Plato, but directly to Proclus on several occasions, so we know for a fact that he had immediate access to Neoplatonic source material.

Recorde published a series of books that built on another and were concerned with mathematics and the practical use thereof: The Grounde of Artes (1543), explaining elementary arithmetic, laid the foundations for The Pathwaie to Knowledge (1551), concerned with elementary geometry, which, through The Gate of Knowledge (dealing with measurement and the quadrant; not extant), led into The Castle of Knowledge, treating astronomy and the sphere, and then finally to The Treasure of Knowledge (not extant and probably never published; possibly about astronomical navigation or advanced cosmography). The titles and their sequence are already interesting, because Recorde here clearly establishes a hierarchical order of the different mathematical disciplines and their application.

As already mentioned above, we do not know for sure what exactly the final book would have dealt with. Both The Pathwaie to Knowledge and The Whetstone of Witte mention a book on navigation as a future work by Recorde. On the other hand, in The Castle of Knowledge he promises to write more about cosmography. The latter option seems to be the more fitting one as the ultimate objective and upper end of the disciplinary hierarchy, because this order is more than just a neat metaphor for the fact that one indeed needs certain mathematical skills in order to understand and apply astronomy in a more sophisticated way. It implies that astronomy has a higher status, some sort of deeper meaning compared to the tool-like quality of the mathematical disciplines that it presupposes. This notion, hinted at in the titles and their sequence, is further elaborated in the preface:

“Who soeuer therefore […] doth minde to auoide the name of vanitie, and wishe to attayne the name of a man, […] looke vpwarde to the heavens, as nature hath taught him, and not like a beaste go poringe on the ground and lyke a scathen swine runne rooting in the earthe. Yea let him think (as Plato with diuers other philosophers did trulye affirme) that for this intent were eies geuen onto men, that they might with them beholde the heavens: whiche is the theatre of Goddes mightye power, and the chiefe spectakle of al his diuine workes. There are those visible creatures of God, by which many wise philosophers attained to the knowledge of his inuisible powers. There are those strange constellations, by which Job doth prooue the mightye Maiestie and omnipotency of God.”

Astronomy’s special status above other mathematical studies or their application stems from the belief that only astronomical knowledge enables human beings to fully grasp “the mightie Maiestie and omnipotency of God”, and that is ultimately what distinguishes humans from the “beaste[s that] go poringe on the ground”. The notion that astronomy is a “road to God” is not entirely new to (Neo)Platonic thought and can, for example, also be found in Ptolemy. However, it is remarkable that Recorde highlights Plato by naming him directly, and it is a concept that resonates deeply with Neoplatonic ideas. The top-down structure of Neoplatonic metaphysics is complemented by an epistemological bottom-up movement. In this context that means that humans can perceive the heavens, the bodies therein and their movement as part of the sensible world. Via Soul as intermediary, those perceptions of “visible creatures” are relayed to Intellect, which matches them to their respective Platonic forms of the intelligible realm, thereby rendering the “inuisible powers” behind the physical phenomena ‘knowable’. And because this process leads up the metaphysical hierarchy towards the One as the ultimate source, and the One is identified in Christian Neoplatonism with God, knowledge is the way to come closer to God.

Sources used:

- Deane, Thatcher, "Instruments and Observation at the Imperial Astronomical Bureau during the Ming Dynasty," Osiris, vol. 9, 1994, pp. 126-140.Hall, Marie Boas. The Scientific Renaissance, 1450-1630. Dover Publications, New York, 1960.

- Hallyn, Fernand. The Poetic Structure of the World: Copernicus and Kepler. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1990.

- Johnson, Francis R., and Sanford V. Larkey. “Robert Recorde’s Mathematical Teaching and the Anti-Aristotelian Movement.” Huntington Library Bulletin 7 (1935): 59-87.

- Johnson, Francis R. Astronomical Thought in Renaissance England: A Study of the English Scientific Writings from 1500 to 1645. Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1937.

- Johnston, Stephen. “Recorde, Robert (c. 1512–1558), mathematician.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 03. Oxford University Press. Date of access 10 Sep. 2021, <https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-23241>

- Johnston, Stephen. "The Castle of Knowledge: Astronomy and the Sphere." Robert Recorde: The Life and Times of a Tudor Mathematician, 2012, pp. 73-92.

- Pankenier, David W., “The Cosmo-political Background of Heaven's Mandate.” Early China, vol. 20, 1995, pp. 121–76.

- Patterson, Louise Diehl. "Recorde's Cosmography, 1556," Isis, vol. 42 (3), 1951, pp. 208-218.

- Roberts, Thomas G. The Castle of Knowledge. TGR Renascent Books, 2009.